Some things have changed since 1966. Some never will.

LOUISIANA La. - If you ask former University of Louisiana basketball mentor Beryl Shipley to name the best player he ever coached, the answer may surprise you.

Most of you will figure the answer to be Dwight Lamar, the only player in NCAA history to lead both the College Division and Major College Division in scoring. You would be wrong. Others might choose Roy Ebron, the player Sports Illustrated magazine once tabbed as the second-best big man in the country behind Bill Walton. They would also be wrong. Or maybe you were thinking along the lines of Larry Fogle, who led the nation in scoring after transferring to Canisius or perhaps Marvin Winkler, who finished his Cajun career fourth in scoring and second in assists.

Great players, true, but still not the correct answer.

Why not? Because Elvin Ivory was that good.

Ivory, a 6-8 postman from Birmingham, Ala., was considered to be one of the 10 best high school players in the country in 1965. George Raveling was close to signing him at Villanova, while Oscar Robertson was phoning almost daily in an effort to sway the youngster toward Cincinnati. But, Ivory had other plans.

"Look, I could have gone anywhere, and I knew it," says Ivory today. "But, I went to USL (now University of Louisiana) because I was thinking of my race, not myself. My parents were big into integration - we attended the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, the one that got bombed. I was very aware of being black and knew that if I chose a school in the South, I could help make a difference."

Shipley and assistant coach Tom Cox recruited Ivory, along with Winkler and Leslie Scott, a Loyola-Chicago transfer by way of Baton Rouge, to become the first African-American athletes to play in the Deep South for a predominantly white college. A dozen years earlier in 1954 (just two years after the Supreme Court's landmark Brown v. Board of Education ruling), the school became the first in the entire South to integrate its student body, a process so quiet and peaceful that hardly anybody even noticed.

But, everyone noticed this time.

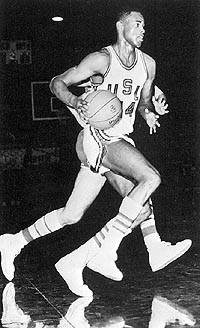

Elvin Ivory as a freshman in 1966"At USL, I used them, and they used me," says Ivory. "All they wanted was a black to play basketball for them; they didn't give a damn about me personally. It was about one thing, about how bad they wanted me to go there. I used to tell them all the time, you're not doing me any favors."

If Ivory sounded angry, he was and, I think, still is. Though his words are calm and well thought out, there is an undeniable air of resentment concerning his years here. He is certainly candid as he speaks of the past and insists to this day that the decision to choose USL over Villanova was the worst mistake of his life.

"I had a lab instructor in biology give me an 'F,' and he was up-front about it. He said, 'We don't want you here.'"

But for two years, Ivory stuck it out and excelled on the basketball court. Though the Cajuns lost on the road to nationally ranked Houston, Ivory was generally considered to have outplayed Cougar All-American Elvin Hayes and even blocked four of Hayes' shots.

"Oh, boy, those were the days," he says. "The (Louisville) game against Butch Beard and (Wes) Unseld, that was fun, too. Sure, there was some stuff that happened, but it never really bothered me. Because I was fairly arrogant, you know? I knew I was good, and if you couldn't play, I was gonna let you know."

Today, he lets people know if they can act or not. As an assistant director in Los Angeles, he's perhaps Hollywood's tallest member of the respected Directors' Guild.

"My first show was The Jeffersons and the rest is history. I got into the Guild and did Silver Spoons, Diff'rent Strokes, Give Me a Break, Facts of Life and Who's the Boss?, all of them with Norman Lear.

"It was just me, dealing with people."

All things considered, he's certainly had enough practice. He once told Scott, his teammate, that he couldn't play, period, and why was he here, anyway?

"I said, 'You shoot all the time and you don't make nothing, what are you doing?'" he remembers, laughing. "'Why don't you give me the ball?'

"But I was trying to motivate him, get him to wake up. There was a lot of pressure on us to be good, and if you're black and you're not good, then we've got a problem."

Elvin Ivory was always good enough. But, I can't help thinking that his days at USL were numbered not only because of a culture's intolerance, but also because of his own.

"I was a little more mature than the average person of that age, so I could read through them, and they weren't that smart anyway," he says. "It was like, how can you tell me about basketball when you can't play?

"Yeah, I was a handful."

Original Link Broken

Times of Acadiana

Out of Bounds

Don Allen

Sports and Movies

Quote

Quote.jpg)